What’s Your Name?

Facebook has been revolutionary in its way of connecting people around the world. That doesn’t mean it has no faults.

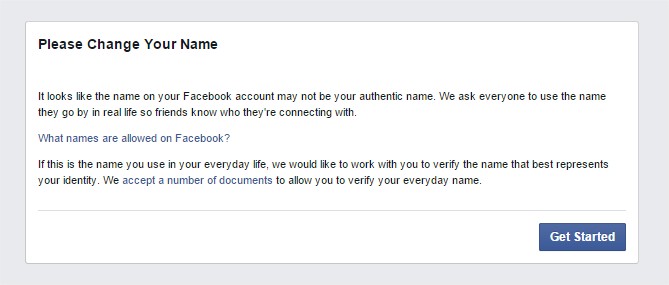

Users who Facebook suspects to have a fake name may be greeted with this message upon logging into their account.

February 26, 2019

I have never liked going by my real name on social media. Ever since I created a Twitter account in 2013, I’ve felt a strange urge to list my name as something that it isn’t. Maybe it’s because using my real name allows just about anyone to find me, and at the time, I was being bullied, so the thought of someone finding a personal account with my real name felt nauseating to me.

So, when I joined the social media platform, I chose to go by Rain, the name of a character I created. I also used a photo from a Japanese cartoon I liked. With a name most people wouldn’t associate me with, combined with the lack of identifiable features, I felt safe. I felt secure. I felt like I belonged somewhere in a time where I didn’t fit in.

On Facebook, my account was initially under my birth name. But by 2015, I was still uncomfortable with the thought of my real name being on social media for people to find me. By this point, I had joined various writing communities – a place where I have met amazing people that have become my closest friends, but also extremely toxic individuals who would try to ruin your life over not writing with them. Because of this, I decided to change my name on Facebook, too. I thought that if Twitter let me choose my name, Facebook would, too.

My thoughts were wrong; I found my account disabled in June of 2015, only two months after making the change. I was devastated; not only did that account have memories dating all the way back to when I was nine years old, but I was friends with people who had recently passed away and couldn’t accept my friend request. It was then that I learned of their policy about names.

“Facebook is a community where everyone uses the name they go by in everyday life,” their Help Center said. They went on to explain that their policy protects people against phishing and scams, as well as impersonation. I was shocked; I was never comfortable with using my real name, and yet I was forced to do so on one of the most popular social media sites at the time. However, I couldn’t fight it; the only way to get my account back was to submit an ID; being an emotional 13-year-old, I thought the invasion of privacy was a small cost for the memories left on my account. So, I did just that, and my account was back within 24 hours. However, it was under my real name, the one thing I had been trying to prevent. I found I could no longer change it, leaving me unable to fight something I felt was unjust.

I knew I wasn’t alone in this; Facebook had one billion active users in 2012, so my problem surely couldn’t be unique. It wasn’t, either; Facebook has been repeatedly called out for its policies. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Community has discussed how their policies unfairly target transgender individuals, as well as drag queens, for their chosen names or pseudonyms, all because it is not the name listed on their birth certificate. This is ridiculous; when transitioning, adopting a new name is a right of passage for trans individuals (and even other members of the LGBT community) when they are trying to transition, and yet, Facebook has made it harder for them to be taken seriously, all because they don’t go by their real name. Not only that, Facebook’s policy disregards people’s real names if they do not fit the specifications they expect from an individual. Because of their closed-minded policy, Native Americans – who may not have common names – have been told their names “violate [their] name standards.”

“Perhaps Facebook is not aware but an entire generation of Native children lost their cultural names after the Dawes Act of 1887 was implemented,” Samuel White Swan-Perkins, an organizer for the #MyNameIs coalition, told Vice in 2015. “Whatever the name is, it’s not for you to question. Natives deserve better treatment, as do our LGBTQIA and other allies.”

While his words were spoken in 2015, they still ring true today. Six years after I first created that Twitter account, I still don’t go by my real name for reasons I am not comfortable sharing, and I have created a new Facebook account under my preferred name. I’ve clashed with the company multiple times over this, from simple name change requests to having my account disabled overnight.

I haven’t relented, however; my name may not be on any documents or IDs, but who is Facebook to tell me what I can and cannot go by? Why should they dictate what constitutes the difference between a real name and a fake one? Their policies alienate people with unique names, those in the LGBT community, and anyone who simply doesn’t feel comfortable using their birth name for whatever reason.

Again, Facebook’s argument is that its policy protects individuals from phishing and scam attempts, as well as impersonation. This would be a good argument if their approach actually worked. I cannot name how many times I’ve gotten spam messages from random people on Facebook. It’s certainly more than I’ve gotten on Twitter, I can say that now. So despite Facebook’s claim that these unfair policies protect people, Twitter allows its users to change their names to the most ridiculous of things, from “J.J Bittenbinder” to “Triple Meat Whataburger Liberal,” one of those things not even being an actual name.

Instead of targeting people who already face struggles in everyday life, Facebook should absolutely change its policy. Despite its numerous attempts to revise its policy on real names, this problem clearly still exists, and it needs to be dealt with soon. Because in time, these people will just stop trying. They’ll stop making new accounts, they’ll stop trying to get their name confirmed, they’ll just give up and move on to a better, more inclusive platform that doesn’t harass them about whether or not their name is legitimate. And that right there will mark the end of Facebook.

Astrid✨ • Feb 26, 2019 at 4:16 pm

Absolutely agree.

Ive had the same problem since 2014-2015

Another thing Facebook doesn’t protect its users from stalkers or harassers

I cannot use my legal name on Facebook for numerous reasons

one being that its uncommon and gets called fake,

another being that my abuser(s) and stalker(s) know my legal name and will continue marking several Facebook accounts to harass me and stalk me

Blocking and reporting doesn’t help