Mrs. Murtaugh: The Utilitarian Job of Teaching

December 5, 2018

Emily Murtaugh is living her dream. One day during her pre-kindergarten years in Kansas City, her dad was building a deck. Naturally, she decided to organize the two-by-fours laying in the yard into rows, and soon there were stuffed animals seated dutifully at their desks, eager to digest the momentous knowledge their teacher had prepared. Years later, she was mimicking professional teachers and the lessons they gave, equipped with all the necessary supplies and a home basement. She doesn’t know if this surprising calling came from Barney or Sesame Street, but she has always known that this drive to teach was innate.

Known now as Mrs. Murtaugh by her students at Dakota Ridge, the English teacher has a front-row seat to the controversy that has gripped the high school, Jefferson County, Colorado, and the country for that matter. Becoming a mother in September 2017 as well, Murtaugh is embroiled in the firestorm that is school safety, which if current events are any indication, will not be leaving the limelight for a long time.

“I want my child to have a sense of fear — I don’t want her oblivious to the world she lives in, but I hate how much she has to fear,” Murtaugh says, adopting a decidedly serious demeanor, “I go [to public school] every day hoping I come home to her. I’m really afraid I’ll have to send her to school hoping she comes home to me.”

While her concerns about safety never quite go away, Murtaugh’s first priority after the class bell rings is to provide her students with the opportunities they need to be successful. She graduated from the University of Colorado at Boulder with a Master’s in both English and Psychology.

“I actually had a college professor who was very about the structures, and how there was a right way versus a wrong way to teach. I didn’t agree with that,” she says with a not-so-hidden smirk, “I thought that every year you had to change how you taught based on what the kids needed. So, her and I didn’t see eye to eye. And one day, she told me I should choose a different profession! In my first year teaching, I was nominated for teacher of the year in the district, and I so badly wanted to write her back and say ‘nanner, nanner.’”

Murtaugh is quick to practice what she preaches, her enthusiasm and passion always on display during lessons as she enunciates poetically while walking circles around the classroom. She firmly stands by the belief that no student should feel unloved or denied opportunity, no matter their background.

Coming from a swirling, all-over-the-place upbringing, Murtaugh has experienced a number of perspectives that would be harder to digest than a cinder block if you tried to do so all at once. Born in Arizona, she moved to Kansas City, Indiana, and several cities in Colorado during her childhood.

“Moving affected my perspective, personally because I felt like I met a wide range of kids. I met a lot of families, backgrounds, and I was always the new kid. So even having that perspective, it made me look at how other people would feel or if they understand me. It developed a lot of fear, but ultimately, moving allowed me to see the strengths, weaknesses, good, bad, light, dark of the world around us,” she says, “To go from Colorado Springs to Boulder even showed me a change in beliefs, values, and political views especially.”

In her colorful classroom at Dakota Ridge, Murtaugh is the opposite of a new student. While the room she occupies on navy days is completely decked out with literary memorabilia, pictures of happiness, and a wonderfully hefty bookshelf, her concern shows through, with a black safeguard magnet placed over the door latch, with inescapable worst-case scenarios engraved in her mind. To her, nothing is more integral to the improvement of safety than cooperation and communication.

“Dr. Jelinek does a great job of supporting his staff and his students and communicating with the community. When we have walkouts for issues that, of course, I believe our students should support, he works with student government. He works to make those acceptable in our community, to make everyone safe during those times and to make sure our focus is on education,” she says with conviction. “If our students are afraid, Deputy Dave, Dr. Jelinek, our admin team — we are all aware. Everything gets spread to us, and we know what’s going on.”

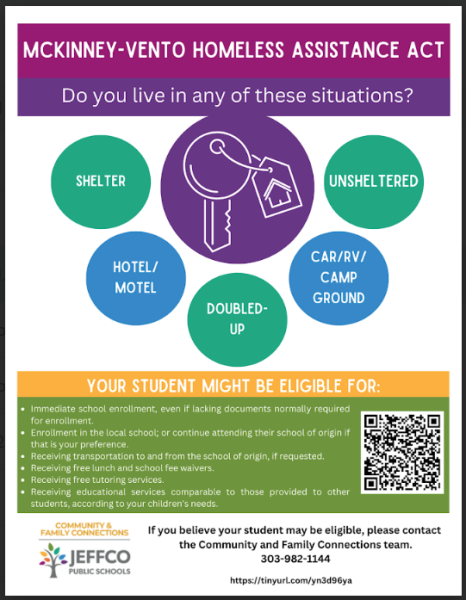

“I am concerned if we don’t, as a community, start putting equal value on education, that we are going to have less and less expectations for our students; therefore, I’m concerned with what’s going to happen with our society,” Murtaugh pragmatically says. The continued funding of Dakota Ridge and other schools in the district is central to the society of increased school safety Murtaugh sees in the near future: “Without the outside resources it’s going to become more and more difficult to do our jobs in order to suit what students need. So in five to ten years, I think there will still be great teachers, there will still be great administration, but I’m concerned that we will not have the resources and the outside support in order to make that happen.”

“Our schools can’t stay back twenty years ago and expect our students to move twenty years forward,” Murtaugh says authoritatively.

Mrs. Murtaugh believes not only that funding and outside assistance can facilitate a culture change in schools across the nation, but also that teachers are the first line of defense in a student’s life. She recalls a catalyst that shaped her views on teaching, specifically that it is composed of far more than just the material.

“My first year of teaching, I was 22, and my seniors were 18. Long story short, I had a student who was not on track to graduate. He had made very, very poor choices at school, in his personal life, and with the law. He and I, we got along, we understood each other, and I realized that’s what I was there for. We worked during my plan, after school, before school, during lunch on make-up work in all of his classes. We got him on track for graduating. He showed up to my final without pencil, paper, anything to take this test, and he just sat there in front of me. I was not proud of myself — I used bad words and I told him to get out of my classroom. I was disappointed in him. I had to call my supervisors and tell them I used bad language toward a student, that I didn’t know what to do, and I went out in the hallway and he was still there, he had not left. I cried, he cried, and he apologized, and we went back in and we started over. My supervisor told me, ‘Emily, you showed him that it is possible to still be loved even when you are angry, even when you have made a bad choice.’ So I keep it in my head that even when my kids make bad choices, when they come into my classroom I have to give them the opportunity for success. I don’t set up my students for anything they can’t achieve.”